Frederick Merk, Teacher and Scholar:

A Tribute

Rodman W. Paul

Western Historical Quarterly IX (2): 141-148, April 1978.

At the request of WHQ, Rodman W. Paul wrote this tribute to Frederick Merk (August 15, 1887 - September 24, 1977). Paul is Harkness Professor of History at the California Institute of Technology and is President of the Western History Association.

At the close of last September, when members of the Western History Association were making final revisions in the papers they would soon be reading at the annual convention in Portland, the profession lost one of the most effective and best loved of all those who have taught western history in American universities. Frederick Merk died at the age of ninety in Cambridge. His whole career had been at Harvard, to which he came as a graduate student in 1916 to study under Frederick Jackson Turner. Turner, of course, had made his fame with work done at the University of Wisconsin, from which Merk himself graduated in 1911, but the timing of Turner's departure for Harvard was such that "you had escaped me in Madison," as Merk later remarked in a letter to his great mentor.{1}

Between receiving his bachelor's degree in 1911 and winning in 1916 the Edward Austin fellowship for study at Harvard, Merk was on the editorial staff of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin, for which he edited a volume of Civil War documents in 1912 and, much more significantly, wrote a definitive monograph on the Economic History of Wisconsin during the Civil War Decade, published by the society in 1916, a volume that has preserved its value so well that it was republished in revised form in 1971. Harvard accepted this book as Merk's dissertation, and Merk was able to move directly into intensive study under Turner and other members of the Harvard faculty.

{1} Frederick Merk to Frederick Jackson Turner, Cambridge, July 4 [1927], Turner Papers, Huntington Library. The Merk-Turner letters cited here are all from this collection.

He must have made a decisive impression, for Turner began to involve Merk both in teaching in Turner's famous History 17, "The Westward Movement," and in coediting the notable List of References on the History of the West, which from the time of its publication in 1922 was for many years the most important bibliography on that subject. Merk viewed his mentor with reverence and with deep personal feeling. In a letter to Turner's wife in 1926 he declared, "I have never had greater affection for any man, {2} while a year later, when he was writing to Turner himself to comment on Carl Becker's essay on Turner in Master of Social Science, Merk said:{3}

[In History 17] you would say something, a sentence or two, with particular impressiveness, with "that lifted flash of the eye" which Becker describes … [and] I used to glory at the thought that I was in a kind of secret communication with you, that you were giving out something that only a few were privileged to see, and this spurred me on.

The affection and respect must have been mutual, for in 1921 Turner caused Harvard to offer Merk an instructorship, under terms which meant that Merk would be sharing History 17 with Turner and would soon be offering the first half of the general introductory course in American history (with the second semester taught by Edward Channing). The remainder of Merk's duties would be to teach "the second half of a course in American institutional and constitutional history, of which Professor [Charles Howard] McIlwaine [sic] gives the first half. {4} In short, Merk, who had received his Ph.D. in 1920 (and had won Harvard's Toppan Prize in that year) was launching into his teaching career in association with some of the best-known American historians of the day.

Although he had been offered a post with higher rank at the University of Illinois, there was no question in Merk's mind as to what he would do. To Turner he wrote: "My heart was set on Harvard, for I saw there unrivalled opportunities for research under your guidance, the privilege of associating with a great history faculty, and the chance to teach a superior body of students. {5}

With his heart's desire thus fulfilled, Merk settled down to intensely hard work in preparing and teaching his courses. That he succeeded is demonstrated abundantly. Although he published very little, Harvard promoted him to assistant professor in 1924, to associate professor in 1930, to full professor in 1936, and to the distinguished Gurney professorship in 1946. The fact that he moved so steadily up the professional ladder despite publishing only a few articles and editing one book, Fur Trade and Empire: George Simpson's Journal (1931), should give pause to any departmental chairman who insists on applying promotional rules in a purely mechanical, undiscriminating fashion, for Merk became one of Harvard's most respected teachers. Undergraduate and graduate students alike crowded into History 17, which Merk took over entirely after Turner retired in 1924; graduate students never failed to fill Merk's seminar; and the number of beginners who listened to Merk's introduction to American history (History 5) must have been high up in the thousands.

{2} Merk to Mrs. Frederick Jackson Turner, Cambridge, June 29, 1926.

{3} Merk to Turner, Cambridge, July 4 [1927].

{4} Turner to President Elmer George Peterson of Utah State

University, np.; November 6, 1923 (typed copy).

{5} Merk to Turner, Rome, May 7, 1921.

Turner, for all his originality of mind and attractive personality, had not been so notable a teacher at Harvard as one might have expected. {6} Merk far surpassed his mentor in his appeal to the highly critical Harvard audience, and he did this in a way that Harvard admires most: not by showmanship but by thoroughness of preparation, acuity of analysis, and clarity of presentation. Merk never lectured or wrote about any subject until he had mastered all of the printed and manuscript sources – and I mean literally all – nor until he had asked himself the meaning and significance of what he was about to say and had studied the relationship of the episode in question of what came before and what was to follow. When at least he was momentarily satisfied, he would put his knowledge together in lectures that were notable for their clarity and were rich in detail without ever seeming overcrowded.

His delivery should not have been impressive, and yet it was. The New York Times' obituary referred to him as "the wispy professor with the high-pitched voice, {7} to which one might rejoin that Lincoln's voice also lacked resonance, and yet Lincoln is generally regarded as having done pretty well. For each lecture Merk came to the podium clutching a sheaf of notes written out in full with a fine-pointed pen and in that crabbed, crowded handwriting so familiar to his students. During the lecture he would move away from the reading stand to point out features on the maps that he used so constantly, or to step forward closer to the audience for a moment, as if by proximity to give deeper thrust to some major point. The listener was not distracted at all by "the high-pitched voice" of which the New York Times spoke. I have virtually verbatim lecture notes of both History 5 and History 17, taken in the early 1930s, and upon rereading them now, more than forty years later, I still find myself becoming totally absorbed, despite recognizing places where points of view have become dated or where newer understandings have been published by later writers.

Merk's students nicknamed History 17 "Wagon Wheels," and they viewed the course and its proprietor with an affection that Merk's mentor, Turner, had not won. The New York Times was right in saying that "Wagon Wheels" left an indelible impression on generations of Harvard students." It was said that when finding themselves scheduled to be in Boston, busy executives long out of college would rearrange their appointments so as to leave time for a quick trip across the river to Cambridge to hear Merk lecture again in History 17.

What was the key to the success of this quiet, undemonstrative professor? In a single word, integrity. He had the kind of honesty that is usually described as "transparent." It simply was not conceivable that Frederick Merk would have distorted the evidence that he was presenting, or that he would have made an assertion without having proof of its validity, or that he would have been guilty of superficiality. Nor was it conceivable that he would have been willing to lecture on a subject for which he did not feel – and impart – genuine enthusiasm.

{6} Ray Allen Billington, Frederick Jackson Turner: Historical, Scholar, Teacher

(New York, 1973), 385.

{7} New York Times, September 28, 1977.

So it is as a teacher – one of those rare persons whom we call "a great teacher" – that he will be most remembered. But Merk himself was not satisfied to be so known. He wanted to be recognized also for the research scholar that he in fact was. He shared with Turner a perfectionism that made him a slow, careful, and reflective writer, never quite satisfied that he had all the evidence, never ready to call the job done. At the same time his unusual devotion to his teaching made research and writing almost impossible during term time at Harvard. After many months of despair, Merk wrote to Turner in 1930 to describe his mood during the previous year:{8}

"I was in a state almost of despondency over the progress of my work, particularly over the fact that Harvard was converting me against my will into a teacher and an administrator, and choking off my research instincts … Accordingly last December I wrote to [Professor Arthur M.] Schlesinger resigning my post. I rested my resignation on the ground that my tastes and abilities, such as they were, were in the direction of research, that at Harvard I was forced into the mold of teacher and administrator which did not fit me and which was increasingly distasteful to me."

Faced by the loss of a valued teacher, the Harvard history department hastily recommended Merk for promotion to full professor a year ahead of the normal time. Reluctantly, Merk agreed to return for one more year, though he gloomily predicted that "if I continue as a teacher, my years will continue to be barren as a scholar.{9}

At the time when he contemplated resigning, Merk was temporarily free of family responsibilities and thus felt able to risk living on the cramped budget of a research scholar. He had not married and being over forty marriage did not seem likely. A person with great loyalty to his family, he had brought his parents to Cambridge to live with him during the last half dozen years of their lives, when their needs were great and their means small (the father was an artist). His parents now dead, Merk felt independent. But soon after resuming work at Harvard, Merk learned that his brother had come down with an "advanced case of tuberculosis, complicated by other difficulties," and would need financial help. This, Merk wrote to Turner, is what "anchors my ship, and which permits me to postpone for another year at least the hard decision as to what to do with the future.{10}

Harvard helped by persuading others within the department to assume Merk's collateral, nonteaching duties. Much more important was an unexpected development that lifted Merk from his depression and saved the scholarly world from losing a fine teacher. In 1931 Merk was writing to Turner that:{11}

"This year I have had a very happy 20 course [individual studies] with a graduate student of Radcliffe, Lois Bannister … She and I have met on common ground in our admiration for your writings, and this past term we have found many other interests in common. Our conferences recently have not always been confined strictly to history, and I have just persuaded her to let me give her a diamond ring."

{8} Merk to Turner, London, March 1, 1930.

{9} Ibid.

{10} Merk to Turner, Cambridge, January 5, 1931.

{11} Merk to Turner, Cambridge, May 10, 1931

Has there ever been a more charming description of a scholarly courtship? The resulting marriage proved to be a singularly happy one. When the present writer also decided to marry at a much later age than most, Merk firmly encouraged me: "You will find that there are great rewards in late marriage!" The Merks had two children, a son and a daughter, and that, too, helped to keep Merk teaching. When Merk agreed to continue teaching after he had reached retirement age, he wrote to me: "You will find that having children to educate is a great stimulus to continue teaching!"

After retiring in 1957 Merk turned to the batch of topics for which he had accumulated masses of material that had been only partly exploited hitherto in occasional scholarly papers. Mrs. Merk, who had been a college history teacher as well as a doctoral student, unselfishly devoted herself to collaborating with her husband so that these incomplete projects could at last be prepared for the printer. Alfred Knopf, most distinguished of American Publishers, made it his personal interest to publish these books in handsome editions, and at the moment of Merk's death, the Knopf firm was revising Merk's lecture notes for the Wagon Wheels course into still another book. Thus in the end the fruits of Merk's years of meticulous research began to reach the scholarly world. This outpouring of books in Merk's post-retirement years will give readers everywhere a chance to savor something of the quality of the man's mind and personality, but to his students his remarkable accomplishment of the latter days has been unnecessary: they already knew and loved him.

MAJOR HISTORICAL WORKS BY FREDERICK MERK

The Labor Movement in Wisconsin during the Civil War (Madison: Wisconsin Historical Society, 1915).

Economic History of Wisconsin during the Civil War Decade (Madison: Wisconsin Historical Society, 1916; 2nd ed., 1971).

List of References on the History of the West. With Frederick Jackson Turner. (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1922).

"The Oregon Pioneers and the Boundary," American Historical Review, XXIX (July 1924); also in Oregon Historical Review, XXVIII (December 1927).

Fur Trade and Empire: George Simpson's Journal … 1824-25; together with Accompanying Documents, ed., (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1931; rev. ed., 1968).

"British Party Politics and the Oregon Treaty," American Historical Review, XXXVII (July 1932).

"Snake Country Expedition, 1824-25: An Episode of Fur Trade and Empire," Oregon Historical Quarterly, XXXV (June 1934); also in Mississippi Valley Historical Review, XXI (June 1934).

"The Snake Country Expedition Correspondence, 1824-25," ed., Mississippi Valley Historical Review, XXI (June 1934).

"The British Corn Crisis of 1845-46 and the Oregon Treaty," Agricultural History, VIII (July 1934).

"British Government Propaganda and the Oregon Treaty," American Historical Review, XL (October 1934).

"Eastern Antecedents of the Grangers," Agricultural History, 23 (January 1949).

"The Genesis of the Oregon Question," Mississippi Valley Historical Review, XXXVI (March 1950).

"The Ghost River Caledonia in the Oregon Negotiation of 1818." American Historical Review, LV (April 1950).

Albert Gallatin and the Oregon Problem: A study in Anglo-American Diplomacy (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1950).

Harvard Guide to American History, co-author (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1954).

"The Oregon Question in the Webster-Ashburton Negotiations," Mississippi Valley Historical Review, XLIII (December 1956).

"Presidential Fevers," Mississippi Valley Historical Review XLVII (1) (June 1960).

"A Safety Valve Thesis and Texas Annexation," Mississippi Valley Historical Review, XLIX (December 1962).

Manifest Destiny and Mission in American History; a Reinterpretation (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1963).

The Monroe Doctrine and American Expansionism, 1843-1849 (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1966).

The Oregon Question: Essays in Anglo-American Diplomacy and Politics (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1967).

Dissent in Three American Wars, co-author (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1970).

Fruits of Propaganda in the Tyler Administration, with the collaboration of Lois Bannister Merk (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1971).

Slavery and the Annexation of Texas, with the collaboration of Lois Bannister Merk (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1972).

History of the Westward Movement (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1978).

***********************************************************

**FREDERICK MERK**

Frank Freidel

Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society LXXXIX, 1977

Frederick Merk, one of the most distinguished historians of the westward movement, died on September 24, 1977, a few weeks after his 90th birthday. He was Gurney Professor of History and Political Science emeritus at Harvard University and had been a member of the Massachusetts Historical Society since 1937. Professor Merk was renowned as a teacher up to the time of his retirement in 1957, and was phenomenal in his scholarly productivity during the score of years that followed. At the time of his death he was awaiting galley proofs of the summation of his life's work, History of the Westward Movement, which appeared in July 1978.

Professor Merk, born in 1887 in Milwaukee of a family of German background, early became interested in the migration westward into Wisconsin of settlers both from Germany and from the east. At the University of Wisconsin he became imbued with the spirit of La Follette progressivism, then at its height, which helped give a lasting liberal cast to his views. The celebration of the role of the west in the development of the American nation and institutions, a dominant theme in the essays of Frederick Jackson Turner, also lastingly influenced him. Turner had already left Wisconsin for Harvard. "You escaped me at Madison," Merk wrote him years later, but it was on the advice of Turner and others that Merk undertook his first historical research and writing. After receiving his bachelor's degree in 1911 he had joined the editorial staff of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin and in 1916, without graduate training, published the Economic History of Wisconsin During the Civil War Decade, a path-breaking volume. In it, Merk demonstrated the meticulous, thoughtful scholarship notable throughout his career and developed many of the major themes of his later work. Paul Wallace Gates, one of the most eminent of the Merk Ph.D.'s, has said, "At least a dozen scholars have taken his chapter subjects for long and excellent monographs but none has found error, or, have they altogether replaced his book." It reappeared in a new edition in 1971. At the time, it won him the Edward Austin fellowship for study at Harvard, where the history department subsequently accepted the book as his doctoral dissertation.

At Harvard, Merk studied directly with Turner (and others of the historians of that generation) and in 1921 began to share with Turner the already famous course, the "Westward Movement." After Turner's retirement it became Merk's own and became even more outstanding. Into his teaching, Merk diverted the long hours of painstaking research that had previously gone into his writing. His delivery was unexceptional, indeed rather quiet, but the precision of his organization and evaluation, together with the breadth of the new historical vistas he opened, fascinated his students. They were at the forefront of scholarship on the history of the frontier. Upon his retirement, a former student, one of numerous newspapermen who as Nieman fellows had taken the course, wrote in an editorial, "With wit, wisdom and warmth, with reverence for the minutest fact and the broadest meaning, he relived the westward movement for us and left us all enriched."

By the end of 1929, Merk was so troubled because he was not finding sufficient time for his scholarly writing that he submitted his resignation to Harvard. He was single, in his forties, and could live without his salary. The history department stayed his departure by promoting him to an associate professorship a year in advance and lightening his administrative responsibilities. Subsequently, Lois Bannister began graduate work under his supervision. They discovered, he wrote Turner in 1931, "many … interests in common. Our conferences recently have not always been confined strictly to history, and I have just persuaded her to let me give her a diamond ring." They had two children, a son, Frederick Bannister Merk, and a daughter, Katharine (Mrs. James G. McNally, Jr.) and four grandchildren. Merk not only taught to retirement age but agreed to stay on for several additional years. He wrote a former graduate student, Rodman Paul, who also married late, "You will find that having children to educate is a great stimulus to continue teaching!"

When, almost 70, Merk finally left the classroom, he turned his full, remarkably undiminished energies and enthusiasm into some of the topics upon which he had been gathering data and ideas through the years. His scholarly output, which had been relatively light since he had arrived in Cambridge, became prodigious. Focusing upon the diplomacy and politics of western expansion, he published five volumes between 1963 and 1972. Four of the five were with the collaboration of his wife, and one, partially so. First there was the authoritative Manifest Destiny and Mission in American History: a Reinterpretation (1963). There followed The Monroe Doctrine and American Expansionism, 1843-1849 (1966) and The Oregon Question (1967), a collection of essays. Then 2 more were published, Fruits of Propaganda in the Tyler Administration (1971) and Slavery and the Annexation of Texas (1972).

Well before these last two volumes appeared, Merk was at work upon a project of far greater scope. As early as 1965, he wrote John Morton Blum that he was returning to his first love, the westward movement, "after some years of desertion of it in pursuing the red-haired muse of diplomatic history." Later he and Lois Merk labored for several years upon what was to be his culminating work, not simply publishing his lecture notes, as so many of his followers for years had urged, but incorporating extensive additional research and fresh view-points. There is, of course, also in it much that is familiar to generations of former students with memories of his lectures and his remarkable maps and charts. In publication, Merk did not abandon his role of teacher but will gain a wider classroom.

Both in lecturing and writing, Merk in his precise interpretations of the past often gave new meaning to the present. That was apparent in the most renowned of his papers delivered before the Massachusetts Historical Society at the height of controversy over the Vietnam War when he delineated and evaluated the opposition to the Mexican War more than 100 years earlier. The essay appeared in Dissent in Three American Wars (1970).

When in May 1977 Merk received what was to be the last of the many honors that had come to him, an honorary degree from Clark University, the citation read, "The Indian summer of his professional life has been more fruitful than most men's springtime."

**A Celebration of Frederick Merk (1887-1977)**

John Morton Blum

The Virginia Quarterly Review 54

pp 446-453 Summer 1978

Frederick Merk came to Harvard from Wisconsin. He brought his West with him and nurtured it in Cambridge, as a student, teacher, and scholar, for more than six decades. Born in Milwaukee, he received his bachelor's degree from the University of Wisconsin in 1911, worked for five years on the staff of the State Historical Society, moved to Harvard in 1916 to begin graduate study under Frederick Jackson Turner, won a prize for his dissertation, and in 1921 received his first faculty appointment as an instructor. His cursus honorum brought him in 1946 to the Gurney Professorship. A quarter of a century earlier he had shared the teaching of various courses with Charles H. Mcllwain, Edward Channing, and Arthur M, Schlesinger. A colleague and contemporary of Samuel Eliot Morison, among others, Merk in the latter year of his tenure taught graduate students who are now still a decade from retirement. His career, then, spanned the first three or four generations of professional historians, and his benign and rigorous influence continues to imbue American university classrooms.

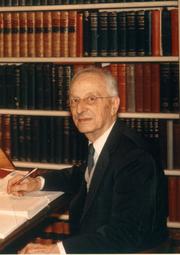

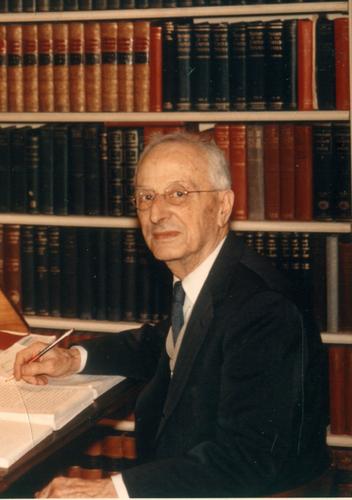

He was a small man, but big-boned, especially his hands, craftsman's hands. He had a singularly narrow face with a large, responsive mouth and inquiring eyes behind unobtrusive spectacles. Winter and summer he wore dark suits, white shirts, dark ties, black shoes, and, on cold days, sometimes a wool cardigan. Even in his eighties his erect posture accentuated his determined walk. His throaty, rather high voice had a penetrating quality, not the least because of his controlled, meticulous diction. He did not smoke or drink alcoholic beverages, he had no small talk, he was never a familiar of his students, never a gregarious hail-fellow, and yet his generosity of spirit, his profligacy with his own time, made every student and colleague who knew him well his debtor.

In March 1977, about five months before his 90th birthday and seven before his death, I knocked on his door at Widener 515 as I had intermittently knocked there for almost 40 years. As he had responded on each previous occasion, so did he respond then:

"Come!" Half invitation, half command.

"Fred," I said as I entered, "how are you?"

A moment's reflection, stock-taking perhaps, then:

"John, I'm tough!"

II

Frederick Merk was tough—physically, morally, and intellectually tough, as tough as a wonderfully gentle man could be. After the Valentine's Day blizzard of 1940, with greater Boston immobilized, Fred Merk snowshoed into Cambridge from Belmont, some five miles, to deliver his nine o'clock lecture on the history of the American West. Up from the river houses at Harvard there walked to join him only half-a-dozen undergraduates, perhaps a tenth of the class. He made no comment at the time, but he never forgot any one of them, not a face, not a name. Physically tough, though illness forced him to miss several lectures the following year. Did he ever miss more?

Intellectually tough, disciplined for seven decades to long days at his desk, to exhaustive efforts in his search for historical data and in precise veracity in their use. He loved his calling and beckoned others to it. To the first meeting of his graduate seminar he always put the same question: "Why do you want to study history?" Some within the class of which I was one replied that they expected, like Ranke, to find truth; others believed history had a special relevance for current issues. Fred had the last word, the only good answer to his own query: "I study history because I like to."

In his shy way he also liked his students. Perhaps those he knew in the early years of his long Harvard career became closer to him than did his postwar flock, But we, too, felt the personal warmth that lay beneath his criticisms, whether those criticisms were admiring or corrective. And annually, at tea at 10 Village Hill Road, Belmont, we sensed the privacy and serenity of his home, the quiet intimacy that he shared with his wife, Lois, (an historian in her own right and in time also his collaborator), and with their son and daughter. He established with each of us a precise relationship as supportive as it was controlled. Most important, he encouraged us in his seminar or in our dissertations to go our separate intellectual ways. Never prescriptive, he responded in kind to our varied enthusiasms so long as they were genuine and disciplined enthusiasms. While he gave us collectively a common lesson about the methods of history, he permitted us individually to wander as we felt we had to, in 1946 one to the triangular trade; another to the young Lincoln in Springfield, Illinois; still another to the Irish-American ward politicians of Jersey City. Even when we were just beginning our apprenticeship, Fred welcomed us as future colleagues.

As chairman of his department during the years of World War II, he wrote many long letters, often in hand, to his students in the armed services. I shall not forget one I received while my ship was en route to Iwo Jima, Several pages long, that letter described in extraordinary detail the provisions of the G. I. Bill of Rights as they would apply to me if I chose to pursue a Ph. D.in history at Harvard, the exact terms according to which I would be admitted to the program, and the various reasons why Fred believed that I should apply. He concluded by urging me to select a topic for my dissertation before I left the Navy. It was some months before I could give that letter my full attention, but once I did, I was moved and flattered by the effort he had made on my behalf, and persuaded by his advice, the chart and compass of my apprenticeship, as it was also for so many others. He was our master.

III

Teaching absorbed Fred Merk, as it did few others on the Harvard faculty in his time. The substance of what he taught evoked the enthusiasm of the undergraduates who filled his classes; the spirit behind his teaching bound his graduate students to him. Shortly after the end of the war, a group of Harvard doctoral candidates had luncheon together in the top floor of the building of the Department of the Interior in Washington, by coincidence the department responsible for so many of the public policies that engaged Fred's professional interests. About to leave the armed services and to return to the academic enterprise, those eating together asked themselves what their various Harvard mentors had taught them. No empirical answer satisfied them. Then the most discerning of the company put it right."I don't know what any one else was teaching," he said, "but Fred taught integrity." So he did, an integrity of mind and process, of the way in which to understand and to write history, an integrity by his standards so severe that perhaps no one of his students could ever achieve it, but a quality he made so important that all of them would try.

The substance and method of history imbued his lectures. As a lecturer he had no equal at Harvard in the field of American history, and few in any other field or any other discipline.(In my own experience, only William L. Langer and F. O. Matthiessen rivaled him.) In the first half of the introductory course, he made each lecture a separate, complete essay. Once when he was ill, his teaching assistant read aloud from the text that Fred had prepared in his characteristically cramped but wholly legible hand. The assistant finished in 35 minutes. Fred's special rhetoric, his sense of the drama of what he had to say, his clarity of thought and emphasis, his use of pauses and repetitions, would, had he been reading that text himself, have consumed easily the allotted 53 minutes. Those qualities of his delivery always did. Gems of synthesis, his lectures combined narrative with analysis, including evaluation of the latest relevant scholarship, invariably indentified by author and title.

He altered his style in only one respect when lecturing in his more celebrated course on the history of the westward movement. There he addressed a topic for as long as he deemed appropriate, perhaps for three or four lectures. In order to remind his students of where they were at the start of each session, he began with a brief summary of the previous lecture, a summary prefaced by the phrase: "At the last hour. . . ." That course, according to Harvard folklore, became known as "Wagon Wheels" or "Cowboys and Indians." It was not so known when I took it in 1941. Then we all called it "Merk." Each extended topic in the course had the attributes of a carefully structured chapter that took its proper place in the commanding book that the total course represented.

That book had the fascination of variety as well as of structure and synthesis. Some parts of it, but not many, derived from Frederick Jackson Turner. I have no recollection of Fred discussing the impact of the frontier on American character or the safety-valve thesis, though he had us read Turner on those subjects. He did give continual attention to sectionalism, and within sections to regionalism, though his ideas about those questions diverged at crucial points from Turner's. Further, his magnificant slides included copies of what he called "the great series on presidential elections" that Turner had prepared. He had many more slides of his own, slides that communicated his insights into political and economic geography, as well as his sense of the relationships among patterns of settlement, varieties of crops, and voting behavior. He had, as he once put it, a "stubborn conviction that for undergraduate and graduate teaching visual aids are, and always have been, a big help. The slides are also a help to me in my writing. I return to them again and again to find information I cannot find elsewhere in convenient form." An incomparable resource, the slides, he said, would ultimately go to the Harvard Archives where they might "help to turn the Harvard Department again into the path" of the study of the history of the West.

IV

As Frederick Merk taught that subject, and as he wanted his students to comprehend it, it included significant excursions into related topics: national politics, of course; economic and business history; the history of agriculture and of agricultural and extractive technology; the history of American foreign policy. His monographs on Manifest Destiny, on the Texas question, the Oregon question, the Monroe Doctrine, studies completed and published, by and large, after he had retired, found an earlier, vigorous, exciting expression in his lectures."Do you recall," one of his former undergraduate students wrote not long after Fred's death, "(did you share) the youthful sensation which came when we first learned that we could learn county-by-county, crop-by-crop, election-by-election the economic and political history of the United States? Some of us . . .loved and admired him." Lots of us did.

Fred's interests again and again influenced at least two generations of his graduate students. So it was, among those who wrote dissertations under his direction, that Paul W. Gates, the most honored among them, made his province Western and agricultural history; Rodman Paul tilled Western fields and worked western mines and their technology; Ralph Hidy and Alfred D. Chandler, Jr., became preeminent in the history of American enterprise, and Samuel Hays in the study of voting behavior; Bradford Perkins pursued issues in Anglo-American relations; Elting E. Morrison provided stunning contributions to both the history of technological innovation and the history of national domestic and foreign policy. Fred Merk never suggested that he made those distinguished scholars what they became, but he delighted in their achievements, which were mirrors of his professional purpose. "I am very proud of my old graduate students," he once wrote, and about what some of them had done, ". . .1 am actually vain."

For their part, they were proud of their relationship to him; they felt his presence in their work just as his undergraduate students felt it in his classrooms. Fred had a kind of monumental quality. It drew to his last lecture, delivered in the spring of 1957, several dozen of his former students, undergraduates and graduates alike. "The turnout Tuesday," he wrote a friend who was there, "was contrary to my expectations. The History Office, at my wish, kept the news of my retirement confidential until such time as an announcement should come through the regular University channels. The announcements did come in the press on Tuesday morning, but already, on the previous day, the news was abroad and I was receiving letters from as far away as Amherst. I felt rather ashamed afterwards that I had not shared my secret. . . ." Only as modest a man as he could have believed that his "secret" would not out, that his former students would not discover their last chance to see and hear him in his sanctum.

V

He had in fact no intention of retiring from history. About five years before that last lecture, one of his former course assistants, by then a professor in his own right at a distant institution, met Fred on a Saturday afternoon in the stacks at Widener Library."Why Jim," Fred said, "what are you doing here on a lovely Saturday afternoon?"

"A young man," came the reply, "has to make his way in the world. And what are you doing here, Mr. Merk?"

"An old man," Fred answered, "has to prepare to die."

That preparation lasted another quarter century. In that time Frederick Merk published the bulk of his contributions to the literature of American history. Most of those books spoke to questions of foreign policy, but the last, destined for posthumous publication, focused on the history of the West. "I have recently returned," he wrote a friend about that book, "to my first love, the "Westward Movement" after some years of desertion of it in pursuing the red-haired Muse of diplomatic history. Now I am done with that indiscretion. . . . Much new writing on the Westward Movement has appeared since I last taught that course and to catch up with it is no slight task. However, I still have all the old devotion to the subject and a little though less, of the energy for it that I once had. If I can apply the spur to myself . . . I may succeed in finishing the job."

Of course he did. Until the day he died Fred Merk remained tough physically, morally, and intellectually, above all, perhaps, tough on himself. For all of us whose dissertations felt his influence and his dedication, he will continue to be, as George Washington was for Henry Adams, a "primary . . .an ultimate relation, like the Pole Star." And so we shall continue to try to dedicate ourselves to his standards, and thus to celebrate him, Frederick Merk, Magister Artibus Historiae.

***

16 works Add another?

Most Editions

Most Editions

First Published

Most Recent

Top Rated

Reading Log

Random

Showing all works by author. Would you like to see only ebooks?

Subjects

History, Oregon question, Territorial expansion, Economic conditions, Foreign relations, Politics and government, Imperialism, Manifest Destiny, Public opinion, United States, Diplomatic relations, Doctrine de Monroe, Expansion territoriale, Frontier and pioneer life, Great Britain, Industries, Monroe doctrine, Northeast boundary of the United States, Political messianism, united states, Politique et gouvernement, Relations extérieures, Sources, Tyler, John, -- 1790-1862, Tyler, john, 1790-1862, United States -- Politics and government -- 1841-1845Places

United States, Wisconsin, Great Britain, Northwest boundary of the United States, Northeast boundary of the United States, Texas, USA, West (U.S.)ID Numbers

- OLID: OL509196A

- ISNI: 0000000081230828

- VIAF: 44425700

- Wikidata: Q5498386

- Inventaire.io: wd:Q5498386

Links outside Open Library

No links yet. Add one?

| September 30, 2020 | Edited by MARC Bot | add ISNI |

| March 31, 2017 | Edited by MARC Bot | add VIAF and wikidata ID |

| April 6, 2012 | Edited by Frederick Bannister Merk | Edited without comment. |

| April 6, 2012 | Edited by Frederick Bannister Merk | Edited without comment. |

| April 1, 2008 | Created by an anonymous user | initial import |