Check nearby libraries

Buy this book

Synopsis

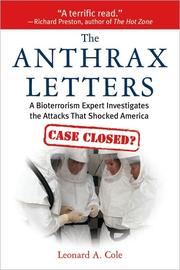

At 2:00am on October 2, 2001, Robert Stevens entered a hospital emergency room. Feverish, nauseated, and barely conscious, no one knew what was making him sick. Three days later he was dead. Stevens was the first fatal victim of bioterrorism in America.

Bioterrorism expert Leonard Cole has written the definitive account of the Anthrax attacks. Cole is the only person outside law enforcement to have interviewed every one of the surviving inhalation-anthrax victims, along with the relatives, friends, and associates of those who died, as well as the public health officials, scientists, researchers, hospital workers, and treating physicians. Fast paced and riveting, this minute-by-minute chronicle of the anthrax attacks recounts more than a history of recent current events, it uncovers the untold and perhaps even more important story of how scientists, doctors, and researchers perform life-saving work under intense pressure and public scrutiny. Updated with new information about Ivins and a series of upcoming Congressional hearings into the FBI's conduct in this case, The Anthrax Letters amply demonstrates how vulnerable America was in 2001 and whether we are better prepared now for a bioterror attack.

Check nearby libraries

Buy this book

Previews available in: English

Showing 1 featured edition. View all 1 editions?

| Edition | Availability |

|---|---|

|

1

A Medical Detective Story THE ANTHRAX LETTERS: A leading expert on bioterrorism explains the science behind the anthrax attacks

2009, Skyhorse Pub.

in English

1602397155 9781602397156

|

aaaa

Libraries near you:

WorldCat

|

Book Details

First Sentence

"[Excerpt from Chapter 6] For 14 years, beginning in 1977, Henderson served as dean of the Johns Hopkins School of Public Health. But before then he had already become a legendary figure in public health. From 1966 to 1977 he directed the World Health Organization's campaign to eradicate smallpox. His last year as director was the last year that a naturally occurring case of smallpox occurred anywhere in the world. As he sat at home that Sunday afternoon, the phone rang. "Dr. Henderson? Hello, Dr. Henderson. This is Eric Noji, calling from the Department of Health and Human Services [HHS]. Secretary Tommy Thompson asked me to contact you immediately." Dr. Noji, a specialist in "disaster medicine" at the Centers for Disease Control had recently come up from Atlanta to help establish an Emergency Command Center in the Secretary's office. "Secretary Thompson would like you to come over for a meeting at 7 o'clock." Henderson had worked in the previous administration as Deputy Assistant Secretary at HHS under Donna Shalala. He had never met Thompson and much appreciated the invitation. "Seven tomorrow morning? Or do you mean tomorrow evening?" Henderson asked. "No, no, no. Tonight!," Noji answered. Henderson caught the sense of urgency. "Yes, of course I'll be there." Soon after, he was driving south on Interstate 95 for the hour-long trip to Washington, D.C. Once in the city, he worked his way quickly along Independence Avenue -- Sunday traffic is light. As he approached Third Street, the open mall on the left offered a stunning view of the Capitol building. To the right, still on Independence Avenue, stood the Hubert H. Humphrey Building, the headquarters of HHS. The seven-story structure, constructed 25 years earlier, is covered with recessed windows that give the appearance of a giant waffle. Henderson parked on the street and walked to the building. As he entered the lobby, high on the wall to his left he could see a portrait of Humphrey and a gold-leaf inscription. The text declares that the manner in which a government treats children, the elderly, the sick, and the needy is, in Humphrey's words, "the model test of a government." Six floors up, Henderson got off the elevator and turned right. Before him was a glass partition beyond which lay the red-carpeted suite of Secretary Thompson. He was escorted by Noji into Deputy Secretary Claude Allen's conference room. Propped up on a rectangular conference table were a computer laptop and a portable printer "donated" by Dr. Noji -- a rudimentary command center soon to be vastly expanded. A couch stool in front of one wall, and soft chairs were off to the side. "I'm very glad you're here," Secretary Thompson said to Henderson. They were joined by Allen, Noji, and Dr. Scott Lillibridge, who had just been appointed Director of the Command Center. Thompson began the discussion by inviting comments about the current situation. Lillibridge and CDC's Noji were absolutely convinced that there would be a terrorism sequel to the September 11 attacks. But what form would it take? Henderson recalled the moment: "...We sort of worked our way through the discussion. Doing something with an airplane again was going to be much harder now than it had been, we decided. I think we all came to the conclusion that it could very well be a biological event. And it was quite apparent to me that this was Thompson's view too..." The secretary rose from his seat and paced back and forth. "He was obviously extremely distressed," Henderson said. Then, referring to his contacts in the White House, Thompson said, "They just don't understand." "What don't they understand?" Henderson asked. "Biological weapons," Thompson answered. Secretary Thompson repeated his concern, emphasizing that the country was "unprepared, grossly unprepared. For a biological attack." During the next two weeks, Henderson was repeatedly invited back to confer with Thompson, Lillibridge and Noji about the possibility of further terrorism. Then, on October 4, Bob Stevens, in Florida, was diagnosed with anthrax. The same day federal and state authorities publicly dismissed bioterrorism as a likely cause of Stevens's illness. Thompson himself emphasized that the case was an isolated incident. He implied that Stevens might have contracted the disease from water: "We do know that he drank water out of a stream when he was traveling to North Carolina last week." Thompson's closest aides, Claude Allen, NIH's Tony Fauci and Doctors Lillibridge and Noji were caught completely by surprise. When Henderson heard this, he was mystified. Thompson's statement was uninformed. Water is not known to convey anthrax, and drinking would be unlikely to cause the inhalation form of a disease. Having minimized the possibility of bioterrorism, the secretary was later criticized as being naive, as not appreciating the serious implications of the incident. In fact, according to Henderson, Thompson's concerns were very real. Henderson realizes this view seems "contrary to what came out when Thompson got on television and assured everybody that everything was in great shape." But Henderson is convinced that Thompson did not believe everything he was saying publicly: "He did what I have seen happen in many disease outbreaks. The political figure gets out in front and says, 'Everything is under control. Please relax.' You know, to calm everybody down. And that isn't necessarily the right thing to do." What would Henderson have advised the secretary to say that first day? To acknowledge that there is a problem. That there's a lot of work to be done. To say that he will keep in close touch with the public. In other words, be open about it. But the tendency is to say, "Every- thing is in good order. We've got everything under control, so don't worry." I think that's wrong. A few days later the presence of anthrax spores was confirmed on Stevens's computer keyboard and elsewhere in the American Media building, where he worked."

Table of Contents

Edition Notes

REVIEWS:

Named an Honor Book by the New Jersey Council for the Humanities

"The anthrax attacks of 2001 took five lives and terrified a nation. Leonard Cole assumed the massive task of considering how these unprecedented attacks touched us individually and collectively, and he skillfully put them in a context that will help us understand how they unfolded and how we might address the bioterrorist threat in the future. The Anthrax Letters is a compelling human story told with scientific integrity."

-- Senate Minority Leader Tom Daschle (D-SD)

"Mr. Cole's new study is one of the most authoritative of the recent crop of books on the anthrax letters, and it is helped by the author's unfailingly clear writing style, which makes the biological threat of anthrax easy to understand. The narrative Mr. Cole weaves is undeniably intriguing."

-- The Washington Times, November 16, 2003

"... [a] thoroughly researched, detailed, and fascinating book... Anyone interested in learning more about this unique episode in the history of biological warfare would find Professor Cole's book informative and enlightening. The Anthrax Letters is a well-written forensic mystery, much more intellectually challenging, stimulating, and rewarding than any fictional television program."

-- Journal of the American Medical Association, July 21, 2004

"...a lucid and compelling narrative, meticulously and thoroughly researched, which sheds light on our country's recent encounter with bioterrorism. ...[a] comprehensive presentation of the science underlying our encounter with anthrax, of its victims, as well as the role that continued work in the field will play in strengthening our defense against future acts of this kind. ...a laudable work."

-- New Jersey Council for the Humanities, August 2004

"The subject of bioterrorism is probably not high on your holiday reading list, but The Anthrax Letters ought to be. It is absolutely riveting. Here's a promise. Read the prologue and you'll read the book. ... [Cole is] a superb writer and his book reads like a fine-tuned suspense novel. The story, of course, is not fiction, but a true mystery that probes behind the panic of the anthrax attack of 2001. Cole undertook his own, enlightened investigation, and has interviewed all of the surviving victims whose stories--until now--have remained out of the news. There are also fascinating portraits of the doctors, researchers, and scientists who worked behind the scenes amid the storm of events. Like the spores themselves, secrets are swirling, and the author brings them into the light in this inspired account."

-- DingBat Magazine, December 2003

"Disentangling a coherent story from the snarl of conflicting reports, multi-agency responses, blaring headlines, empty leads and the shaky scientific data surrounding the anthrax attacks is no simple task, which makes Cole's accomplished book all the more impressive. As an expert on the intersection of politics and terrorism, Cole (The Eleventh Plague) takes the reader on a captivating, no-nonsense tour of America's public health system... The book also supplies the chilling details that the short-lived media flareup failed to convey... Without even a hint of sensationalism, this disquieting but hopeful book skillfully zeros in on the most crucial issues and scientific advances as well as the heroic individuals who averted disaster while under the intense glare of public scrutiny."

-- Publishers Weekly, September 1, 2003

"[The Anthrax Letters] offers us a wealth of detail on the case -- even as it reminds us how little we know."

-- James P. Pinkerton in Newsday, October 7, 2003

"And while it can at times deliver all the drama of a modern-day thriller, the 240-page book also offers the most complete look available at the still-unsolved mystery of how and why 22 people became infected with anthrax between Oct. 4 and Nov. 21, 2001."

-- Roll Call, October 14, 2003

"[Cole's] storytelling abilities rank with those of Richard Preston, without ever losing sight of the science. His detailed case histories and timelines flesh out the familiar media reports of the October 2001 U.S. anthrax by mail attacks, and give the human side of the tragedy."

-- Lancet Journal of Infectious Diseases, January 1, 2004

"Carefully drawn chronology of the anthrax episodes of September and October 2001. They came and went at such speed and at such an overwhelming time that it is pardonable to remember the anthrax-bearing letters as a bad dream. But five people died from them, and this tight narrative of the events makes it clear that they were a mortal cog in the wheel that led to Homeland Security, Afghanistan, and Iraq. Bioterrorism expert Cole also makes it baldly clear that the letters' nasty cargo might easily have claimed many more lives if health professionals hadn't acted with admirable intuition and dispatch, rising to the occasion like latter-day Minutemen. ... The author sketches vivid portraits of the bacteria, those who were infected, and those whose job it was to counter the threat and prepare the nation for biological attack."

-- Kirkus Reviews, August 2003

"For most of the 22 victims of the anthrax letters, Cole provides extensive detail on the circumstances surrounding their infection, diagnosis, treatment and eventual recovery or tragic death. ... As an expert in bio-terrorism, Cole is at his best narrating the physicians' initial suspicion of anthrax infection, and the subsequent awakening of the massive national response network at the local, state and federal levels. ...Cole provides a fascinating account of how quickly the diagnostic facts of medical science became national feelings of terror."

-- Rocky Mountain News, October 31, 2003

"Cole provides excellent insights into how the attacks affected the victims, their families, and society, revealing the horror, fear, and confusion as well as efforts by the government and public health services to react quickly and appropriately. ... [he] provides a fascinating discussion of the attacks and how they will influence our level of preparedness for the future."

-- Library Journal, November 1, 2003

"The Anthrax Letters is a terrific read. The book is a masterful piece of reporting, written with absolute strength and clarity, and the background research Cole has done is slam-on right, impressive in its detail and insight. Cole talked to all kinds of sources no other reporter was able to reach, and he turned the research into a first rate work of narrative describing the first major bioterror event the modern world has seen."

-- Richard Preston, author of The Demon in the Freezer and The Hot Zone

"Luck perhaps has been most accurately defined as where the road of preparation crosses the road of opportunity. For me, these two paths met when I encountered an ill Bob Stevens on October 2, 2001. Leonard Cole's chronicle of the anthrax attacks records with detailed accuracy the medical epidemiological and investigative aspects of these historical events. His narrative is fascinating, insightful, and thought-provoking."

-- Larry M. Bush, M.D.., Florida physician who diagnosed the first anthrax case

"The most effective antidote to biological terrorism is information. Only frank discussion of our vulnerabilities and preparedness will inoculate us against the most contagious agent we face: fear. Leonard Cole makes an invaluable contribution to that discussion with this in-depth look at the people, places and events involved in the 2001 mail-borne anthrax attacks. When the final chapter is written, and the case is solved, this book will have helped point the way to a safer America."

-- Congressman Christopher Shays (R-CT), Chairman of the Subcommittee on National Security, Emerging Threats, and International Relations

"For those seriously interested in the 'anthrax letter' events, there is interesting and genuinely informative reading... The humanity of the individuals who contracted anthrax is effectively brought home and what they felt and how they and those around them reacted are enlighteningly described..."

-- Bulletin of the World Health Organization, January 2004

"The author has done an excellent job with this investigation and this book is probably the most detailed book on the subject. For those who want the big picture of the anthrax attacks, this book is a must."

-- Counterterrorism Homeland Security Reports, 2004

back to top

Author Biography

Dr. Leonard A. Cole is an adjunct professor of political science at Rutgers University, Newark, New Jersey, where he teaches science and public policy. He is an expert on bioterrorism. Trained in the health sciences and public policy, he holds a Ph.D. in political science from Columbia University. He is a Fellow of the Phi Beta Kappa Society and has been a recipient of grants and fellowships from the Andrew Mellon Foundation, the National Endowment for the Humanities, and the Rockefeller Foundation. Cole has written for professional journals as well as general publications including The New York Times, The Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Scientific American, and The Sciences. He has testified before congressional committees and made invited presentations to several government agencies including the U.S. Department of Energy, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the Office of Technology Assessment. He has appeared frequently on network and public television and has been a regular on MSNBC. He is the author of six books including The Eleventh Plague: The Politics of Biological and Chemical Warfare and, most recently, The Anthrax Letters: A Medical Detective Story.

"The Anthrax Letters is a compelling human story told with scientific integrity."

FORMER SENATOR TOM DASCHLE, RECIPIENT OF AN ANTHRAX LETTER

"A terrific read. This book is a masterful piece of reporting, written with absolute strength and clarity."

RICHARD PRESTON

"This book will have helped point the way to a safer America."

CONGRESSMAN CHRISTOPHER SHAYS

Who mailed the anthrax letters?

Are health and law enforcement officials adequately protecting the country against another bioattack?

-Why are many survivors still sick?

Curious? Read The Anthrax Letters

Biography

Dr. Leonard A. Cole is an adjunct professor of political science at Rutgers University, Newark, New Jersey, where he teaches science and public policy. He is an expert on bioterrorism. Trained in the health sciences and public policy, he holds a Ph.D. in political science from Columbia University. Cole has written for professional journals as well as general publications including The New York Times, The Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Scientific American, and The Sciences. He has testified before congressional committees and made invited presentations to several government agencies including the U.S. Department of Energy, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the Office of Technology Assessment. He has appeared frequently on network and public television and has been a regular on MSNBC. He is the author of six books including The Eleventh Plague: The Politics of Biological and Chemical Warfare. He lives in Ridgewood, NJ.

Classifications

The Physical Object

ID Numbers

Source records

Library of Congress MARC recordLibrary of Congress MARC record

Library of Congress MARC record

Internet Archive item record

Library of Congress MARC record

Better World Books record

Excerpts

For 14 years, beginning in 1977, Henderson served as dean of the Johns Hopkins School of Public Health. But before then he had already become a legendary figure in public health. From 1966 to 1977 he directed the World Health Organization's campaign to eradicate smallpox. His last year as director was the last year that a naturally occurring case of smallpox occurred anywhere in the world.

As he sat at home that Sunday afternoon, the phone rang. "Dr. Henderson?

Hello, Dr. Henderson. This is Eric Noji, calling from the Department of Health and Human Services [HHS]. Secretary Tommy Thompson asked me to contact you immediately."

Dr. Noji, a specialist in "disaster medicine" at the Centers for Disease Control had recently come up from Atlanta to help establish an Emergency Command Center in the Secretary's office. "Secretary Thompson would like you to come over for a meeting at 7 o'clock." Henderson had worked in the previous administration as Deputy Assistant Secretary at HHS under Donna Shalala. He had never met Thompson and much appreciated the invitation. "Seven tomorrow morning? Or do you mean tomorrow evening?" Henderson asked.

"No, no, no. Tonight!," Noji answered.

Henderson caught the sense of urgency. "Yes, of course I'll be there."

Soon after, he was driving south on Interstate 95 for the hour-long trip to Washington, D.C. Once in the city, he worked his way quickly along Independence Avenue -- Sunday traffic is light. As he approached Third Street, the open mall on the left offered a stunning view of the Capitol building. To the right, still on Independence Avenue, stood the Hubert H. Humphrey Building, the headquarters of HHS. The seven-story structure, constructed 25 years earlier, is covered with recessed windows that give the appearance of a giant waffle. Henderson parked on the street and walked to the building. As he entered the lobby, high on the wall to his left he could see a portrait of Humphrey and a gold-leaf inscription. The text declares that the manner in which a government treats children, the elderly, the sick, and the needy is, in Humphrey's words, "the model test of a government."

Six floors up, Henderson got off the elevator and turned right. Before him was a glass partition beyond which lay the red-carpeted suite of Secretary Thompson. He was escorted by Noji into Deputy Secretary Claude Allen's conference room. Propped up on a rectangular conference table were a computer laptop and a portable printer "donated" by Dr. Noji -- a rudimentary command center soon to be vastly expanded. A couch stool in front of one wall, and soft chairs were off to the side. "I'm very glad you're here," Secretary Thompson said to Henderson. They were joined by Allen, Noji, and Dr. Scott Lillibridge, who had just been appointed Director of the Command Center.

Thompson began the discussion by inviting comments about the current situation. Lillibridge and CDC's Noji were absolutely convinced that there would be a terrorism sequel to the September 11 attacks. But what form would it take? Henderson recalled the moment:

"...We sort of worked our way through the discussion. Doing something with an airplane again was going to be much harder now than it had been, we decided. I think we all came to the conclusion that it could very well be a biological event. And it was quite apparent to me that this was Thompson's view too..."

The secretary rose from his seat and paced back and forth. "He was obviously extremely distressed," Henderson said. Then, referring to his contacts in the White House, Thompson said, "They just don't understand."

"What don't they understand?" Henderson asked.

"Biological weapons," Thompson answered. Secretary Thompson repeated his concern, emphasizing that the country was "unprepared, grossly unprepared. For a biological attack."

During the next two weeks, Henderson was repeatedly invited back to confer with Thompson, Lillibridge and Noji about the possibility of further terrorism. Then, on October 4, Bob Stevens, in Florida, was diagnosed with anthrax. The same day federal and state authorities publicly dismissed bioterrorism as a likely cause of Stevens's illness. Thompson himself emphasized that the case was an isolated incident. He implied that Stevens might have contracted the disease from water: "We do know that he drank water out of a stream when he was traveling to North Carolina last week." Thompson's closest aides, Claude Allen, NIH's Tony Fauci and Doctors Lillibridge and Noji were caught completely by surprise. When Henderson heard this, he was mystified.

Thompson's statement was uninformed. Water is not known to convey anthrax, and drinking would be unlikely to cause the inhalation form of a disease. Having minimized the possibility of bioterrorism, the secretary was later criticized as being naive, as not appreciating the serious implications of the incident. In fact, according to Henderson, Thompson's concerns were very real. Henderson realizes this view seems "contrary to what came out when Thompson got on television and assured everybody that everything was in great shape." But Henderson is convinced that Thompson did not believe everything he was saying publicly: "He did what I have seen happen in many disease outbreaks. The political figure gets out in front and says, 'Everything is under control. Please relax.' You know, to calm everybody down. And that isn't necessarily the right thing to do."

What would Henderson have advised the secretary to say that first day? To acknowledge that there is a problem. That there's a lot of work to be done. To say that he will keep in close touch with the public. In other words, be open about it. But the tendency is to say, "Every- thing is in good order. We've got everything under control, so don't worry." I think that's wrong. A few days later the presence of anthrax spores was confirmed on Stevens's computer keyboard and elsewhere in the American Media building, where he worked.

Community Reviews (0)

Feedback?| December 26, 2021 | Edited by ImportBot | import existing book |

| December 21, 2019 | Edited by ImportBot | import existing book |

| April 28, 2010 | Edited by Open Library Bot | Linked existing covers to the work. |

| April 20, 2010 | Edited by WorkBot | update details |

| December 10, 2009 | Created by WorkBot | add works page |