Check nearby libraries

Buy this book

[I]n 1997, the fortieth year after Americans named Sputnik I a "technological Pearl Harbor," who can deny that the space program has been a profound disappointment? Indeed, what surprises me now about ... the Heavens and the Earth is not whatever prescience it may have shown regarding the flaws of the technocratic approach symbolized by NASA, but rather how much I still wanted to believe as late as 1985 that the Space Shuttle might usher in a second Space Age of ineffable potential. In short, I should have been even gloomier than I was.

From today's vantage point the Space Age may well be defined as an era of hubris. Not only did it become obvious in the 1960s and 1970s that "planned invention of the future" through federal mobilization of technology and brainpower was failing everywhere from Vietnam to our inner cities, but that it even failed in the arena for which it had seemed ideally suited: space technology. In the years following Sputnik I, experts assured congressional committees that by the year 2000 the United States and the Soviet Union would have lunar colonies and laser-armed spaceships in orbit. The film 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) depicted Hilton hotels on the Moon and a manned mission to Jupiter (January 12, 1992, was the supercomputer Hal's birthday in the film). In the late 1960s, NASA promoters imagined reusable spacecraft ascending and descending like angels on Jacob's ladder, permanent space stations, and human missions to Mars-all within a decade. In the 1970s, visionaries looked forward to using the Space Shuttle to launch into orbit huge solar panels that would beam unlimited, nonpolluting energy to earth, hydroponic farming in space to feed the earth's exploding population, and systems to control terrestrial weather for civilian or military purposes. In the 1980s, the space station project was revived (to be completed again "within a decade"), the Strategic Defense Initiative was to put laser-beam weapons in orbit to shoot down missiles and make nuclear weapons obsolete, and the space telescope was to unlock the last secrets of the universe. By 1990, a manned mission to Mars by the year 2010 was on the president's wish list, and research had begun on an aerospace plane (the "Orient Express") to whisk passengers across the Pacific in an hour and land like an airplane in Asia.

None of it came to pass. Instead, the dream of limitless progress through government-sponsored research and development began to fade even before astronauts stepped on the Moon.

[...]

But the foibles of Space Age technocracy have been most strikingly exposed in the fate of the regime that made technocracy its founding principle: the USSR. Not only did Soviet space programs keep even fewer promises than the American programs, but the Soviet Union itself crashed and burned.

Nothing has changed our perspective on the political history of the Space Age more than the end of the Cold War. In the 1980s it was still possible to imagine the United States in a mortal race for the "high ground" of space and to argue the pros and cons of the "Star Wars" program. Today, with the Soviet empire gone, the Space Age seems almost coterminous with the Cold War itself. That age was born in the initial competition between the Americans and Soviets to get their hands on Nazi V-2s and their designers. It accelerated in the 1950s as both sides raced for an intercontinental ballistic missile. It took off with Sputnik I, climaxed with the Moon race, declined with detente, and died when the Soviet Union died. [from the Preface to the Johns Hopkins paperback edition, 1997]

Check nearby libraries

Buy this book

Previews available in: English

Subjects

Astronautics and state, Astronautics, History, United States, Soviet Union, Weltraumwaffe, Raumfahrt, Politique spatiale, Histoire, Űrkutatás és politika, Astronautique, Ruimtevaart, Politique gouvernementale, Raumfahrtpolitik, Űrkutatás, Astronautics, history, Outer space, exploration, Technology, Aeronautics & astronauticsPlaces

United States, Soviet Union| Edition | Availability |

|---|---|

|

1

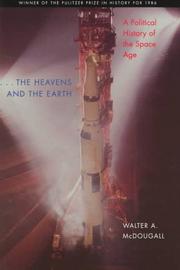

The Heavens And the Earth: A Political History of the Space Age

January 2001, ACLS History E-Book Project

Hardcover

in English

159740165X 9781597401654

|

zzzz

|

|

2

The Heavens and the Earth: A Political History of the Space Age

1997, Johns Hopkins University Press

in English

- Johns Hopkins paperbacks ed.

0801857481 9780801857485

|

aaaa

|

|

3

The Heavens and the Earth: A Political History of the Space Age

September 1986, Basic Books

in English

0465028888 9780465028887

|

zzzz

|

|

4

The heavens and the earth: a political history of the space age

1985, Basic Books

in English

046502887X 9780465028870

|

cccc

|

| 5 |

zzzz

|

Book Details

Edition Notes

Includes bibliographical references (p. [466]-536) and index.

Originally published: New York : Basic Books, c1985.

Classifications

External Links

The Physical Object

Edition Identifiers

Work Identifiers

Source records

Better World Books recordLibrary of Congress MARC record

marc_columbia MARC record

ISBNdb

Work Description

The book chronicles the politics of the Space Race, comparing the different approaches of the US and the USSR. ...the Heavens and the Earth was a finalist for the 1985 American Book Award and won the 1986 Pulitzer Prize for History.

The work highlights the role of Soviet space achievements in spurring the US into mounting its own space efforts to prove the superiority of the American political and economic system, while at the same time adopting the technocratic methods of the Soviet Union in order to do so. McDougall defines technocracy as the state funding and managing technological change for its own purposes. He finds that President Eisenhower took a skeptical point of view on the idea of adopting technocracy in the United States, as he opposed committing the nation to a lunar landing and stated that the progress of state managed technology had contributed to a dangerous military industrial complex in his farewell address. Yet Eisenhower fought against the tide, because by the time he left office the federal research and development budget had increased by 131 percent over the last five years. Gradually the idea of state managed technological progress went from being considered a violation of local freedoms to an accepted part of the federal government’s responsibility. McDougall makes clear that he did not view this in positive terms, as this perceived responsibility trampled the traditional American value of limited government. [Wikipedia]

Excerpts

Links outside Open Library

Community Reviews (0)

History

- Created April 1, 2008

- 13 revisions

Wikipedia citation

×CloseCopy and paste this code into your Wikipedia page. Need help?

| December 19, 2023 | Edited by ImportBot | import existing book |

| November 15, 2023 | Edited by MARC Bot | import existing book |

| November 25, 2020 | Edited by MARC Bot | import existing book |

| October 10, 2020 | Edited by ImportBot | import existing book |

| April 1, 2008 | Created by an anonymous user | Imported from Scriblio MARC record |